Genetic adaptation likely to have occurred over many generations

Mussels from the Kiel Fjord were discovered to be able to adapt to ocean acidification. In a comparative experiment, they were less sensitive to increased carbon dioxide concentrations than their counterparts from the North Sea.

A team of scientists from GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research Kiel, Alfred Wegener Institute, University of Bremen and Senckenberg Institute studied this long-term genetic adaptation to the evolving environmental conditions.

When it comes to the effects of ocean acidification, the Baltic Sea is a unique open-air laboratory. It is apparently also a “training pool” for the mussel Mytilus edulis.

Over time, the population in the Kiel Fjord has adapted to the seasonal acidic content in the western Baltic Sea.

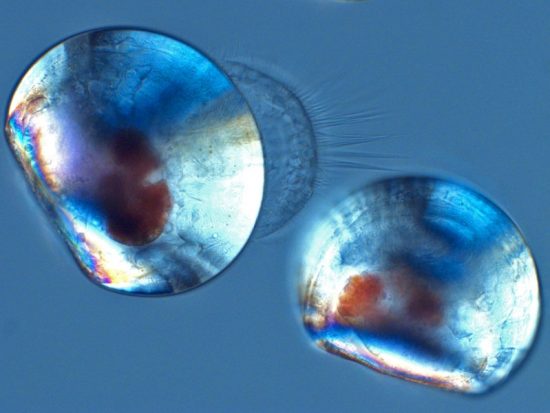

In a comparative experiment, the mussel's larvae formed calcareous shells faster than their counterparts in the North Sea. In addition, more of the mussels from the Kiel Fjord survived. In addition, a complementary, three-year multi-generational experiment suggests that this adaptation was not achieved within a few generations, but over several decades, perhaps even centuries or millennia.

The results of the two experiments were published in the current issue of the Science Advances journal.

For the comparative experiment, mussels were taken from the Kiel Fjord in List on Sylt. They were acclimatised to the environmental conditions

in the North Sea. Their larvae, together with the larvae from the North Sea, were then placed in environments at current carbon dioxide concentrations (at 390 microatmospheres, with an extreme level of 2,400 microatmospheres).

The high concentration of carbon dioxide occurs regularly in the Kiel Fjord, when the wind transports low-oxygen and carbon dioxide-rich water to the surface. This is expected to occur more frequently as a result of climate change.

At higher carbon dioxide concentrations, both larval populations developed their first mussel shell at a slower rate. The shells were also smaller. The larvae from the Kiel Fjord were more robust and had higher survival rates.

“The distinct differences between the Kiel and Sylter mussel larvae suggest that the long-term genetic adaptation has played a decisive role in their

survival and their ability to construct shells,” said lead author Dr Jörn Thomsen in German. “From previous analysis, we know that the two populations also differ genetically.”

However, it is still unknown when the genetic adaptation took place. “It could have taken place in recent decades when climate change, over-fertilization and other factors led to an increase in acidification and rising fluctuations in acidity,” said co-author Dr. Frank Melzner in German.

“It is also possible that the genetic differences, from which the Fjord mussels benefitted from, were formed thousands of years ago. The lower salt content of the Baltic Sea has always influenced the carbonate level in the same way as acidification does today.”

Compared to those from the North Sea, the Baltic Sea mussels were already exposed to lowered concentrations of dissolved calcium carbonate, which they needed for shell construction, and hence they had to adapted accordingly.

Link to the study

Mares

Mares 4th May 2017

4th May 2017