The characteristics of the water masses in the Nordic Seas are expected

to change due to the Earth's higher temperatures and melting glaciers.

To find out more about the effects of these changes, scientists turn to

similar periods in the past.

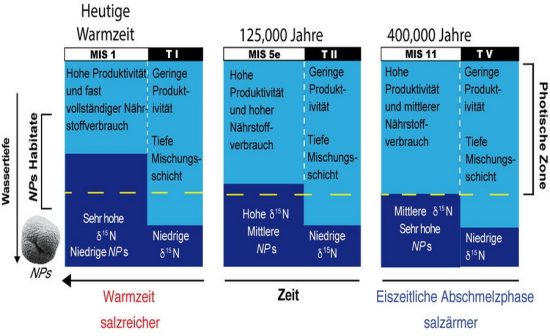

Two recent studies show that the water

properties in the Nordic Sea had varied considerably during the

different interglacials.

Whether in Norway, Iceland or Greenland: the glaciers are melting in

the North Atlantic and European Nordic Seas, releasing large quantities

of freshwater.

Every year, the summer ice cover of the Arctic shrinks

as well, and this also affects the amount of freshwater in the northern

sea between Iceland and Spitsbergen.

In this region, dense, salty water

from the Atlantic sinks into the depths of the sea and flows southwards

whilst near the seafloor. Among other things, this recirculation drives

the Gulf Stream and its branches, and is essential for the European

thermal balance.

The presence of more freshwater in the seas may also

affect the currents.

To predict the future effects of climate change, scientists are looking

into the climate changes of the past.

Completed warm spells are

considered good models for the warming-up season we are currently in.

Two new studies – one by GEOMAR Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research

Kiel, the Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Center for Polar and

Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven and the Hong Kong University, with

the support of the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ),

Utrecht University (The Netherlands) and the University of Victoria

(Canada) – now show independently that the state of the Nordic Seas

differs significantly during different interglacials. At the same time,

they provide fresh insights into these important processes at different

warm periods of Earth's history.

One of the studies, published in the scientific journal Geophysical

Research Letters, attempted to reconstruct the surface salinity in the

Greenland Sea and the European North Sea during a warm period around

400,000 years ago. For this purpose, the researchers used sediment

cores extracted from the seabed south of Spitzbergen.

The new data shows that the ocean surface in the central Nordic Seas

was substantially colder 400,000 years ago. In addition, the layers

near the surface were very low in salt, probably due to the continuous

melting of the Greenland ice sheet and freshwater input from the

Arctic. These processes led to the formation of a thicker, low-salt

layer at the surface, which pushed the Atlantic surface water flowing

in from the south to greater depths.

In the second study, published in the journal Earth and Planetary

Science Letters, a research team led by Dr Benoit Thibodeau from the

University of Hong Kong investigated the nutrient utilisation in the

surface waters of the Greenland Sea and Norwegian Sea during three

interglacial periods between 400,000 years ago and the present.

“The

major changes of nitrate utilisation recorded here thus suggest that a

thicker mixed-layer prevailed during past interglacials, probably

related to longer freshwater input associated with the preceding

glacial termination,” said Dr Thibodeau.

Although the two studies were independent of each other and used

different research methods, the results obtained were quite similar,

indicating that the thickness of the surface layer directly controlled

the depth flow of the Atlantic water layer on its way to the Arctic

Ocean, said co-author and paleo-oceanographer Dr Henning Bauch, from

GEOMAR and AWI.

“The results not only call for caution when using older interglacials

as modern or near-future climate analogues, our findings also help to

better understand the effect of freshwater input on climate-sensitive

ocean circulation sites like those in the Nordic Seas,” he added.

For more information see here

Links to the studies: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2016.09.060 - http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070294

Mares

Mares 5th December 2016

5th December 2016