Findings indicate changes in equatorial undercurrent.

October 2015 saw one of the strongest measured El Niño occurrences in

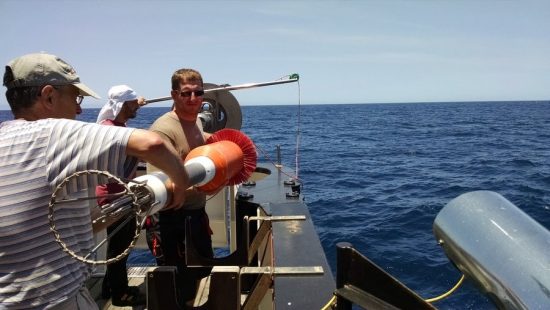

the eastern Pacific. Scientists from Kiel travelled on board the

research vessel Sonne to the low-oxygen regions east of the Galapagos

Island and along the coast of Peru to gather new hydrographical data

that gave rise to new insights into the impact of El Niño on the oceans.

In just a span of several years, El Niño has caused the largest natural

temperature fluctuation in the tropical Pacific; the impact of this has

been felt globally, leading to abnormal temperature increases in the

central and eastern equatorial Pacific. It is accompanied by droughts

and floods in various parts of the world; in 2015, the intensity of

such occurrences was particularly strong, but it has since reduced in

intensity. At the end of 2016, La Niña is expected to follow. This is

El Niño’s counterpart and will lead to colder extremes of climate in

the affected regions.

Last autumn, at the peak of El Niño, scientists from GEOMAR Helmholtz

Centre for Ocean Research Kiel went on an expedition to the eastern

equatorial Pacific to investigate the influence of El Niño on ocean

currents and the buoyancy of the deep water off Peru.

The results of their research, published in the Ocean Science journal,

shows that the equatorial current system has changed greatly. Author of

the study Dr Lothar Stramma from GEOMAR said that in 2012, the team

discovered that the speed of the equatorial undercurrent was almost 11

million cubic metres per second in the eastern Pacific. Three years

later, it had decreased to 0.02 million cubic metres per second.

“The nutrient measurement off the Peruvian shelf shows nutrient-rich

water of lower bouyancy from the deeper water layers, with this effect

spreading southward. A reduced lift [less bouyancy] leads to less

biological productivity and this has massive consequences for the

otherwise productive fisheries in the region,” added Prof Dr Hermann

Bange. In contrast, higher oxygen content was detected in the usually

oxygen-poor regions of the eastern Pacific. This is caused by the new

flow and water mass distributions during the El Niño. There is no sign

of any weakening of the observed long-term decrease in the oxygen

content of the tropical oceans.

The results, together with computer models, are now being used to improve predictions about El Niño.

More information: www.geomar.de

Mares

Mares 18th July 2016

18th July 2016