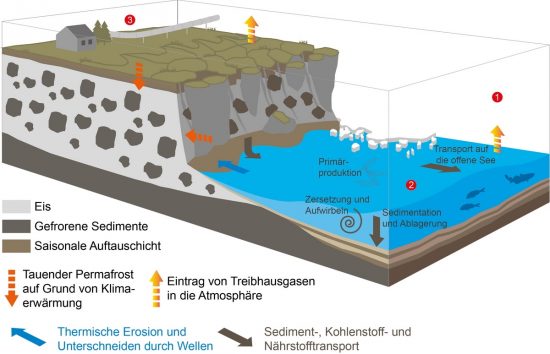

The thawing and erosion of the arctic

permafrost coasts has increased so drastically in the past that more

than 20 metres of land is consumed by the sea every year at some

locations. The earth masses that get removed in the process

increasingly blur the shallow water areas, and release nutrients and

pollutants. However, the consequences of such processes on life in the

coastal zone and on traditional fishing areas are unknown.

In a paper in the January issue of Nature Climate Change, the

scientists at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar

and Marine Research (AWI) are calling for more attention to be focussed

on the ecological consequences of coastal erosion. According to them,

an interdisciplinary research programme involving policy-makers and

inhabitants of the Arctic coasts is required.

Indeed, the difference could not have been greater. During winter, when

the Beaufort Sea freezes around the Canadian permafrost island of

Herschel Island, the seawater in the sample bottles appear crystal

clear. Then, in the summer, when the ice floes are melted, and the sun

and waves wear away the cliff, the seawater sample becomes a cloudy

broth.

“Herschel Island loses up to 22

metres of coast each year. The thawed permafrost slides down into the

sea in the form of mudslides and blurs the surrounding shallow water

areas so much that the brownish-grey sediment plumes reach many

kilometres into the sea,” said AWI researcher Dr Michael Fritz.

His observations of Herschel Island can now be applied to large parts

of the Arctic. Permaforst coasts now make up 34 percent of the coasts

worldwide. Particularly in the Arctic, its soil contains a lot of

frozen water, which keep the sediments together, much like cement.

However, if the permafrost thaws, the binding effect fails, releasing

the sediments which are then washed away by waves.

In the process, greenhouse gases like methane and carbon dioxide are

released, thus leading to even more global warming. Many nutrients and

pollutants like nitrogen, phosphorous or mercury are found within the

eroded material. As these substances enter the ocean, they are further

transported, degraded or accumulated, permanently altering the food

chain.

“We can until now only guess

the implications for the food chain. To date, almost no research has

been carried out on the link between the biogeochemistry of the coastal

zone and increasing erosion, and what consequences this has on

ecosystems, on traditional fishing grounds, and thus also on the people

of the Arctic,” said Dr Fritz.

As such, he, together with Dutch permafrost expert Jorien Vonk and AWI

researcher Hugues Lantuit, is calling on the polar research community

to systematically investigate the consequences of coastal erosion for

the arctic shallow water areas.

“The

processes in the arctic coastal zone play an outstanding role for four

reasons. Firstly, the thawed organic material is decomposed by

microorganisms, producing greenhouse gases. Secondly, released

nutrients stimulate the growth of algae, which can lead to the

formation of low-oxygen zones. Thirdly, the addition of organic carbon

increases the acidification of the sea, and fourth, the sediments are

deposited on the seabed or are transported to the open ocean. This has

direct consequences for the biology of the sea,” they said.

Link to the study

Mares

Mares 18th January 2017

18th January 2017