Exceeding critical temperature values can

lead to collapse of the ice sheet and strong rise in sea level

A future warming of the Southern Ocean due

to increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere could affect the

stability of the West Antarctic ice sheet. This would cause global sea levels

to increase by several metres.

A collapse of the West Antarctic could

have taken place in the last interglacial period 125,000 years ago, a time when

the polar surface temperature was about two degrees Celsius higher than it is

today. This is the conclusion drawn after a series of model simulations by

scientists of the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and

Marine Research (AWI), now published online in the journal Geophysical

Research Letters.

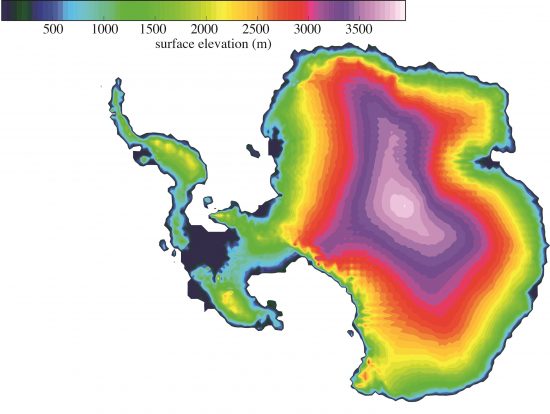

The Antarctic and Greenland are covered by

ice sheets that store more than two-thirds of the worlds freshwater. As rising

temperatures melt the ice, the global sea level has been rising and threatening

coastal regions. Scientific findings show that Antarctica already contributes

0.4 millimetres to the annual sea level rise. The latest world climate

assessment report (IPCC 2013) makes it clear that the development of ice masses

in the Antarctic is not yet sufficiently understood. Therefore, the climate

modellers of the AWI have analysed changes in the Antarctic ice sheet in the

last interglacial period to come up with these findings for future projections.

"Both, for the last interglacial

period about 125,000 years ago and for the future, our study identifies

critical temperature limits in the Southern Ocean: if the ocean temperature

increases by more than two degrees Celsius compared with today, the

marine-based West Antarctic Ice Sheet will be irreversibly lost. This will then

lead to a significant Antarctic contribution to the sea level rise of some

three to five metres,” said John Sutter, AWI climate scientist

and main author of the study. This increase would take place only if global

warming continues as before.

“Given a 'business-as-usual' scenario of global warming, the collapse of the

West Antarctic could proceed very rapidly and the West Antarctic ice masses

could completely disappear within the next 1,000 years,” said Sutter.

Professor

Gerrit Lohmann, head of the research project, added, “The core objective of the study is to understand the dynamics of the West

Antarctic during the last interglacial period and the associated rise in sea

level. It has been a mystery until now how the estimated sea level rise of a

total of about seven metres came about during the last interglacial period.

Because other studies indicate that Greenland alone could not have done it.”

The new findings provide useful data on

how the ice sheet could behave in the wake of global warming. According to

model calculations, the ice would shrink in two waves. The first would lead to

the retreat of the ice masses that float in the coastal area of Antarctica and

stabilise the major glacier systems of the West Antarctic. With this loss, the

ice masses lying behind the ice sheet and the ice flow into the ocean

increases. As a result, the sea levels would rise and the grounding line

retreat. The rate at which ice flows into the ocean would increase, leading to

rising sea levels and the retreat of glaciers. A stable intermediate state can

be achieved once a mountain ridge under the ice temporarily slows down the

retreat of the ice masses.

If

the ocean temperature continues to rise or if the grounding line of the inland

ice reaches a steeply ascending subsurface, then the glaciers will continue to

retreat even if the initial stable intermediate state has been reached. This

would eventually lead to a complete collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

According to Sutter, two maxima could be found in the reconstructions of the

rising sea levels, and the behaviour of the West Antarctic in their newly

developed model could provide the explanation for them.

In

their study, the climate scientists had used two models: a model that includes

various Earth system components like the atmosphere, oceans and vegetation, and

a dynamic ice sheet model that comprises the basic components of an ice sheet

(floating ice shelves, grounded inland ice on the subsurface, the movement of

the grounding line). Two different simulations were used with the climate model

for the last interglacial period to feed the ice sheet model with the necessary

climate information.

Emphasising

the challenges involved in making good estimates, the scientists said that a

reason for the considerable uncertainties when it came to projecting the

development of the sea level, was that the ice sheet did not simply rest on the

continent in steady state but was subject to dramatic changes.

They

continued, “Some feedback processes, such as between the ice shelf areas and

the ocean underneath, have not yet been incorporated into the climate models.

We at the AWI as well as other international groups are working on this full

steam.”

By

improving our understanding of the systematic interaction between climate and

ice sheets, we would be able to answer one of the main questions of current

climate research and for future generations: How steeply – and quickly – can

the sea levels rise in the future?

Link

to study: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016GL067818/full

Mares

Mares 12th February 2016

12th February 2016