Melting glaciers will lead to a reduction of species biodiversity among the benthos (bottom-dwelling

organisms) community in the coastal waters off the Antarctic Peninsula, and

this in turn will impact an entire ecosystem on the seabed. The theory has been

verified through repeated immersion studies,

according to a study by scientists from Argentina, Germany and the UK, and the Alfred Wegener

Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar

and Marine Research (AWI), published in the journal Science Advances.

They

attribute the dwindling biodiversity to increased turbidity of the water. This

occurs when coastal glaciers start to melt due to global warming, resulting in

large quantities of sediment being carried into the seawater.

In the last fifty years, temperatures at the western Antarctic Peninsula have

increased almost five times faster than the global average. Currently, the effects

of how the retreat of glaciers would affect life on the seabed are still poorly

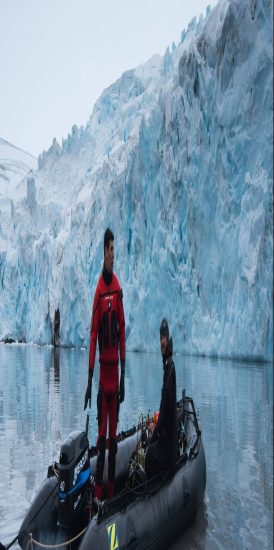

understood. Therefore, scientists at Dallmann Laboratory are currently mapping

and analyzing the benthos in Potter Cove, a bay on King George Island off the western

Antarctic Peninsula. Here, the AWI and the Argentine Antarctic Institute (IAA) operate

Dallmann Laboratory as part of the Argentine Carlini Station. The laboratory has

been monitoring the benthic flora and fauna for more than two decades.

In

1998, 2004 and 2010, divers photographed the plant communities at three

different sites and at different depths. The three locations were: near the

glacier’s edge, an area that experienced less effects from the glacier and in

the cove’s outer edge which experienced minimal influence.

They

also recorded the sedimentation rates, water temperatures and other

oceanographic parameters at the three locations, so that such data could be

linked with the biological data collected. In the end, the researchers

concluded that certain species were very sensitive to high sedimentation rates.

"Particularly tall-growing ascidians like some previously dominant sea

squirt species can’t adapt to the changed conditions and die out, while their

shorter relatives can readily accommodate the cloudy water and sediment cover,"

said AWI biologist and co-author of the study Dr Doris Abele.

"The

loss of important species is changing the coastal ecosystems and their highly

productive food webs, and we still can’t predict the long-term

consequences," she added.

Mares

Mares 20th November 2015

20th November 2015