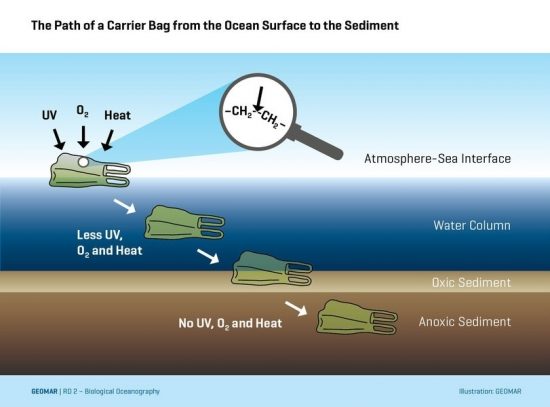

Plastic waste is now found in practically

every part of the world, from the Antarctic coasts to the ocean depths. Faced

with this dire fact of modern life, a team of marine scientists from the GEOMAR

Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, the University of Kiel and the

Cluster of Excellence “The Future Ocean” set out to find out how long it takes for plastics to

decompose.

They placed two common types of plastic

waste – carrier bags and biodegradable bags – in oxic and anoxic sediments for

98 days. The carrier bags were conventional polyethylene bags while the

biodegradable bags were made of compostable polyester, cornstarch and some

undisclosed ingredients. The sediment samples taken from the Eckernförde Bay in

the Western Baltic.

“In

the upper layers of these sediment samples, oxygen was still present, but not

in the lower layers. That is typical for seafloors around the world. […] These

layers also differ in the types of bacteria that live therein,” said marine biologist Alice Nauendorf, author of the

study.

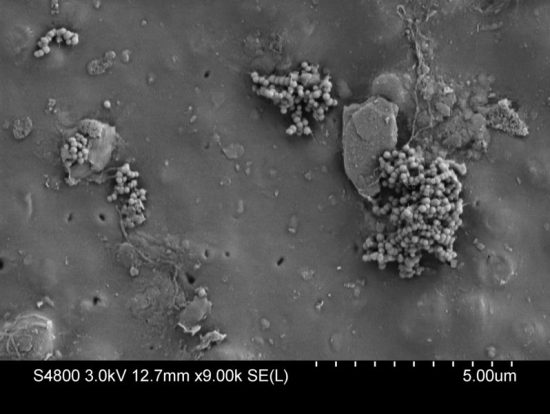

After 98 days, the team examined the

plastic bags for any changes in the material composition, using analytical

methods such as high-precision weight measurements, scanning electron

microscopy and Raman spectroscopy.

Publishing their results in the Marine

Pollution Bulletin journal, the team declared that there was no change in

the material of the bags. “We found no weight loss

or chemical alteration. Therefore, no decomposition of the material is

suggested,” said Professor Dr. Tina Treude, principal

investigator of the study, who now works at the University of California, Los

Angeles.

Nevertheless, the rate at which the biodegradable

bags were colonised by bacteria was significantly faster. “We could clearly see

that the compostable bags were more colonised with

bacteria – in the oxygen-containing layers five times stronger, in the

oxygen-free layers even eight times more powerful than the polyethylene bag,” said Nauendorf.

The reason for the difference is unknown,

but Nauendorf suggested that an antibacterial substance in the polyethylene

bags could have restricted the bacterial colonisation.

Nevertheless, it is obvious from the

research that plastic degradation is a very slow process, and bacterial

colonisation does not guarantee the chemical conversion of a substance. “The study suggests that the seafloor would become a

long-term deposit for plastic waste if we don't stop polluting the seas. Future

studies have to show what impact plastic waste has on benthic ecosystems,” said Professor Treude.

Link to study: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X15302277

Mares

Mares 15th February 2016

15th February 2016