For

the first time, sea ice physicists at the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) have

developed a new method of efficiently measuring the distribution and thickness

of a sub-ice platelet layer in the Antarctic.

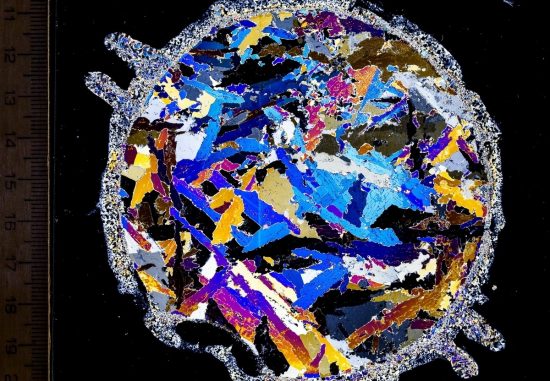

This

layer, called platelet ice, comprises delicate ice crystals beneath the coastal

sea ice. Although it was discovered more than a century ago, very little is

known about it. Nevertheless, the platelet ice is of central importance as it

influences sea ice properties and the associated ecosystem in various ways.

Thus, it serves as an indicator of the state of the melting ice shelves.

Every year, the ocean surrounding the

Antarctic continent freezes to form the sea ice. However, this is not the only

ice being formed. Beneath the surface, at the same time, a layer of loose ice

crystals is formed. Its appearance is similar to the crushed ice found in

cocktail glasses – the difference being that the ice crystals in the platelet

layer are disc-shaped and as thin as one millimetre.

In past decades, scientists discovered

that platelet ice plays a significant role in the sea ice mass balance in some

regions around the Antarctic. The algae that thrive on the platelets serve as

food for the many small crustaceans and fish that seek shelter between the

platelets from predators like seals and penguins.

Because it is concealed beneath the sea

ice, many scientists usually come across platelet ice by accident – for instance, when they drill through the sea ice to measure its

thickness. Now, scientists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre

for Polar and Marine Research, the Jacobs University Bremen and Uppsala

University have developed an efficient method of determining the distribution,

thickness and volume of platelet ice over a large area. Their results have been

published in the latest issue of Geophysical Research Letters.

Previously, electromagnetic (EM) induction

sounding devices were used to measure the electrical conductivity of the

subsurface layers. As the electrical conductivity of the solid sea ice differs

from that of the salty seawater below it, the transition between the two can be

pinpointed.

However, the transition between the sea

ice and platelet ice is less distinct, and conventional EM methods which used

just one frequency were inadequate. Scientists then invented a ground-based,

multi-frequency EM induction sounding device that used several different

frequencies, allowing them to accurately pinpoint the transitions without

having to drill holes through the ice and using measuring tapes.

Using the new device, the scientists

conducted surveys in the frozen Atka Bay, which is located in the Weddell Sea,

near the German research station Neumayer III. The device was placed on a kayak

which was attached to a snowmobile. They then repeatedly drove across the sea

ice of the bay for weeks, several hours at a time.

“One of the things we noticed was that the

evolution of the platelet layer has an annual rhythm,” said AWI sea ice

physicist and co-author Dr Mario Hoppmann. The platelets start to accumulate in

June, as the Antarctic winter starts. The platelet layer grows over the course

of the winter, until it is several metres thick in December. After this time,

it shrinks during the summer.

The researchers believe that platelet ice

plays an important role in the ice regime of the Antarctic. This is because

while the sea ice in Atka Bay has an average thickness of two metres, the

thickness of the platelet layer beneath averages five metres over the course of

a year. In some places, it is even ten metres.

This means that a considerable amount of

ice exists in the form of platelets. According to Hoppmann, “To understand the

situation of the Antarctic sea ice and to assess a possible influence of

climate change, it is likely that more account must be taken of platelet ice.”

Link to study: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2015GL065074/full

Video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cub0w7S7Mh8

Mares

Mares 8th February 2016

8th February 2016 Weddell Sea

Weddell Sea