Higher water temperatures can lead to nitrite accumulation in marine environments worldwide, and this can ultimately disrupt oceanic food webs, according to a new study.

Nitrite is produced when microorganisms consume ammonium in waste products from fertilisers, treated sewage and animal waste. If there is excessive nitrite in the environment, single-celled plants living in the marine environment are affected. This may subsequently have an impact on the animals that feed on them and may even lead to the emergence of toxic algal blooms and dead zones.

This conclusion was revealed in a paper recently published in Environmental Science and Technology.

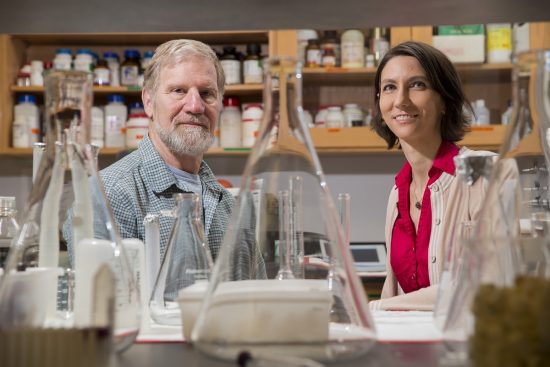

“Rising ocean temperatures are changing the way coastal ecosystems – and probably terrestrial ecosystems, too – process nitrogen,” said co-author James Hollibaugh, Distinguished Research Professor of Marine Sciences in the University of Georgia's Franklin College of Arts and Sciences.

He added that much of the global nitrogen cycle occurred in the coastal zone.

In examining their data collected over the course of eight years, Hollibaugh and researcher Sylvia Schaefer discovered midsummer peaks in nitrite concentrations alongside large increases in the microorganisms that produce it in the coastal waters off Sapelo Island, Georgia. Most researchers believe that this nitrite accumulation is due to oxygen deficiency, but both Hollibaugh and Schaefer think that there is more than meets the eye.

“The paradigm taught when I was in school was that hypoxia, or lack of oxygen, results in nitrite accumulation. But the Georgia coast does not go hypoxic. It just didn't fit,” said Hollibaugh.

In the course of their research, the two scientists discovered that higher temperatures caused single-celled organisms called Thaumarchaea to produce more nitrite.

According to Schaefer, the microorganisms involved in the process were very tolerant to low oxygen levels, adding, “Typically, two groups of microorganisms work in really close concert with one another to convert ammonium to nitrate so that you don't see nitrite really accumulate at all, but we found that the activity of those two groups was decoupled as a result of the increased water temperatures.”

Environmental monitoring data from other locations in the US, France and Bermuda affirmed the association between higher temperatures and nitrite accumulation.

The possible consequences of this may extend beyond coastal water quality management into areas like agriculture.

“The same process, though we didn't look at it specifically, takes place in regards to fertilizing soil for agricultural purposes. It affects farmers and their efficient use of fertiliser – when they should apply it and what form it should be in – and ultimately much of that fertiliser will end up in the waterways, which can lead to algal blooms that choke out other species,” said Hollibaugh.

As a result of nitrite accumulation, more nitrous oxide – a greenhouse gas – is produced, subsequently leading to higher temperatures, and this in turn leads to more nitrite accumulation, and so a positive feedback loop is created.

Hollibaugh concluded, “The information gained from monitoring programmes, like the ones we used to analyse temperature and nitrite data across the country and in other countries, can be used not only to forecast what is going to happen down the road and the longer-term consequences of management decisions, but also to come up with potential solutions for the problem. The data collected by these programs are important for wise management of our resources.”

Herbert

Herbert 7th July 2017

7th July 2017