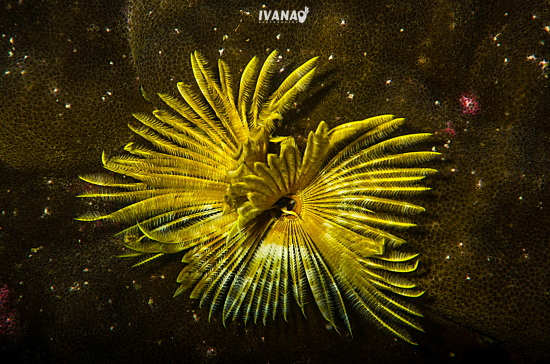

When we think of worms, these colourful, feathery, flower-like creatures are not the first things that come to mind. Their colourful tentacles make them look graceful and sophisticated, representing a wide range of colours and patterns.

Polychaetes mean “many bristles” so these worms are commonly known as bristleworms. Mostly all marine, bristleworms are the largest group of annelids. These segmented worms have their bristles in bundles of two on each side of every segment, with their body composed of quite advanced organs and a nervous system. Their head has less developed organs in comparison to their mobile cousins, but as they are settled and don’t move around; instead of jaws and antennae, they have a crown of specialised feather-like tentacles.

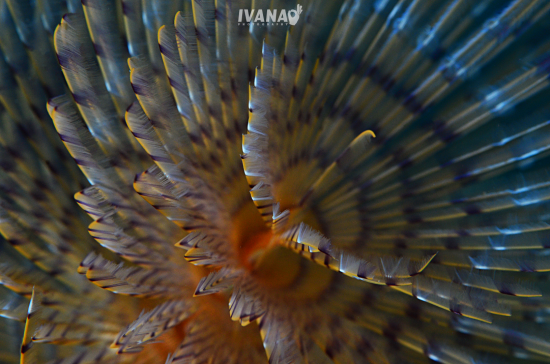

Being sedentary (always in their tubes) they need long tentacles for filtering food that passes by and for respiration. The tentacles are positioned in a circle around the mouth which is called branchial crown which most of the time has an operculum (like a trap door) that closes rapidly when the tentacles are pulled back when the animal feels threatened.

Their feathery tentacles increase their surfaces for higher oxygen absorption and easier trapping of their planktonic food. The little hairs that the tentacles are lined with (cilia) move continually, helping with the transfer of food towards the mouth. The smallest particles caught are eaten, intermediate sized mixed with mucus and used for tube creation, and large particles discarded.

Some worms have double spirals of tentacles which make them look like two worms stuck together, but this illusion just makes them look prettier. Sensory organs such as the eyes are often positioned along the tentacles, so they are very observant and easily startled.

Tube worms are found worldwide except for the polar region. Living in tubes made from calcium carbonate, grains of sand, fragments of shells or mucus and mud they can form quite extensive reefs on the seabed with up to a few thousand individuals cemented together. These reefs are only found in a few locations so far, and we can mainly see individual worms while diving.

As larvae, they settle onto the existing tubes of other worms and also on stones or shells. Once settled the “clump” grows until they can extend their tentacles which they use for filter feeding and breathing. Worms such as the Organ Pipeworm (Serpula vermicularis) form tubes up to 15cm long and 0.5cm wide but some form long thin tubes, other shorter and stubby, the peacock worm’s tube can be long as 25-30cm. Sometimes clumps break off, but as they keep growing they form a hard reef. They grow very slowly and are quite fragile so that any impact can damage them. Trawling for Nephrops can particularly pose a threat to them, but divers should also be careful not to bump into the tubes.

As they love muddy and silty seabeds, trying to take a good picture of them is a challenge as any shadow or movement will cause them to withdraw rapidly, and it takes a while for them to come out again. Photographing tube worms require a lot of patience and perfect buoyancy; any slight movement usually ends in creating a muddy cloud, so a range of skills is necessary to take the perfect tube worm picture.

Text: Bogna Griffin, BSc Applied Freshwater and Marine Biology, GMIT, Ireland

Photos: Ivana Orlovic Kranjc

Ivana and Janez

Ivana and Janez 4th April 2018

4th April 2018 GMIT, Galway, County Galway, Irlanda

GMIT, Galway, County Galway, Irlanda