Why only a few introduced species establish themselves in foreign marine regions

The number of non-native species detected for the first time in marine areas outside their natural habitats is steadily increasing worldwide. Although thousands of species are transported around the globe every day, only a few manage to establish themselves in their new homeland and displace other species. So far, it has been largely unexplained why some species are so successful, while others never quite establish themselves.

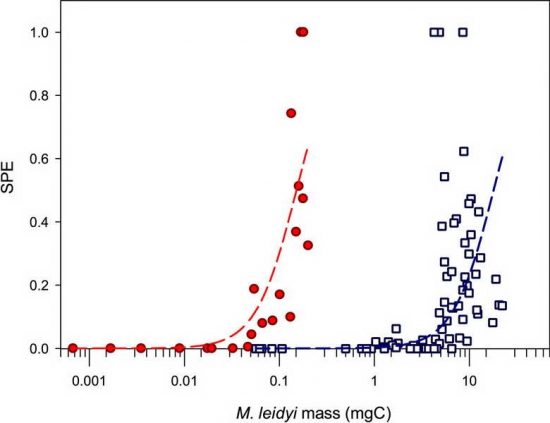

A study conducted by the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, published in the international journal Global Change Biology, shows that the comb jelly (Mnemiopsis leidyi, also known as the sea walnut) multiplies much earlier in a foreign environment than their native cousins in America – on average at 100 times less body mass.

The oceans are changing. In addition to rising temperatures and acidification, more and more marine animals are being transported around the globe – as stowaways in the ballast water tanks of container ships. Hence the number of non-native species in the oceans is steadily increasing and this is giving rise to far-reaching changes. Although only a small fraction of non-native species actually manage to establish themselves, the impact on ecosystems can be devastating.

“In a classical sense, they often show high tolerance for varying environmental conditions, a large food spectrum and an elevated reproduction potential. However, these factors are not sufficient to decide who will be successful in the new habitat and who will not,” said Dr Cornelia Jaspers, Biological Oceanographer at GEOMAR. Most species encounter problems as they have travelled on their own, so there are insufficient partners in the new environment. Thus, achieving a successful reproduction is often in the stars. However, there are other species that are immune to this situation: They are both male and female in one body, so they lay eggs and fertilise the eggs themselves. “These so-called simultaneous hermaphrodites are highly efficient organisms. Theoretically, one animal is enough to establish a new population in a so far un-colonised area – if environmental conditions are good,” said Professor Dr Thomas Kiørboe, Director of the Excellence Centre “Ocean Life” at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU Aqua).

An example of a very successful, invasive species is the comb jelly, also called a sea walnut. It produces more than 10,000 eggs daily and is a simultaneous hermaphrodite. It gained fame in the late 1980s, when its mass appearance in the Black Sea coincided with the collapse of commercial fish stocks. In northern Europe, it was spotted for the first time in 2005 and is very abundant in the Wadden Sea and the Danish Limfjord. In America, where the sea walnut is a native species, a very large variation in its reproductive potential has been observed. This means that some animals reproduce very early, while others become sexually mature when they are larger. The larger an individual is, the greater his or her reproduction potential. However, there is a greater danger of dying before this occurs. Thus, there is a correlation between a) early sexual maturity, coupled with few offspring and a high probability of achieving this, and b) later reproduction, coupled with high egg production rates but a lower probability of achieving this.

Simple mathematical population models, which the authors developed in their study for the sea walnut, show that in native areas, both these extreme strategies have no influence on the individual fitness of the comb jelly. They work equally well to ensure that the animal’s genes are transferred to the next generation. However, the prerequisite for this is that the population is in balance and does not grow, as is to be expected in established populations in an ecological equilibrium. However, invasive species in a foreign environment are characterised by spreading, that is, having positive population growth. Model calculations have shown that the optimal strategy for ensuring this is to reproduce as soon as possible.

Studies of the reproduction strategy in both native and foreign areas and an evaluation of existing literature data has shown that in non-native areas, a much earlier reproduction of the comb jelly takes place. On average, in invaded areas, the jelly multiplies at a hundred times lower body mass. This shows that during an invasion, earlier sexual maturity takes place.

“Up to now, it was underestimated that a high variability of reproductive tactics in the source population would be one of the prerequisites for marine invasive species to be successful," said Jaspers.

“Our study shows that during the establishment phase in non-native habitats, animals with earlier reproduction get selected to sustain a high population growth rate. This is however only possible, as a reduced selection pressure in the native range allows for a large range of reproductive tactics to maintain on population level. Hence, high reproduction rates per se are not the key for successful invaders, but the large variability in reproductive tactics in native habitats and selection for early reproduction in invasive populations make the trick," she added.

Link to the study: doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13955

Herbert

Herbert 19th November 2017

19th November 2017