Jellyfish and related organisms are among the most important predators

The animals of the deep sea have been systematically studied for over 100 years, and scientists are still learning about them. A recent study by MBARI researchers Anela Choy, Steve Haddock and Bruce Robison shows that gelatinous animals are important predators and provides new information on how deep-sea animals interact with life near the ocean surface.

In general, biologists find out what deep-sea animals eat by collecting and dissecting them, and then examining the contents of their stomachs. More recently, scientists have extended on this approach by comparing the ratios of various natural elements in the flesh of deep-sea animals with the ratios of these elements in the tissues of their potential food sources.

To use these methods, scientists have to collect a large number of animals, which is difficult in the deep sea. In addition, soft and gelatinous animals decompose rapidly after being eaten and are often damaged or destroyed when caught with nets.

The MBARI researchers have now chosen a completely new, but relatively uncomplicated approach: they used deep-diving vehicles to observe the feeding behaviour of animals in the deep sea. According to Robison, "This direct approach has never been used systematically before. Unlike other methods, it involves no guesswork and provides very precise information about who eats whom in the deep sea."

Since the late 1980s, MBARI researchers have been using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to study deep-sea animals in their habitat. To date, they have collected over 23,000 hours of deep-sea video footage.

MBARI Video Lab technicians carefully analysed virtually every minute of every ROV dive, identified animals and their behaviour, and entered that information into the Video Annotation and Reference System (VARS) database.

While browsing through the VARS database, the researchers made almost 750 different video observations of animals eating each other.

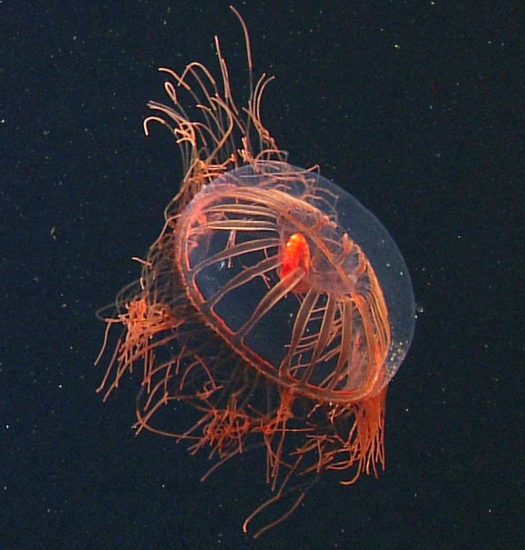

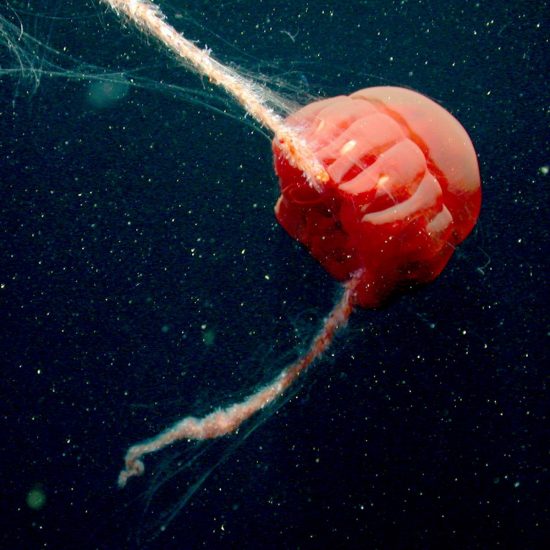

"I was excited to see how our understanding of food webs might change as a result of making direct observations of deep-sea life using an ROV," commented Choy. "The most surprising thing to me was how important gelatinous animals were as predators, and how their unexpectedly complex food habits spanned the entire food web. [...] Our video footage shows that jellies are definitely not the dietary ‘dead ends’ we once thought. As key predators, they could have just as much impact as large fishes and squids in the deep sea!”

Even at depths of up to 200 metres, it was the siphonophorae (related to the Portuguese man-of-war) – not fish or cuttlefish – that were discovered to be the predators most commonly seen in video recordings.

Conversely, the Nanomia bijuga, a small but very common siphonophore, proved to be a specialist which eats almost nothing except krill, essentially competing with blue whales for food.

As can be seen from these examples, the food webs of gelatinous animals include not only deep-sea animals but also those that live near the sea surface. Gelatinous animals have been found in the stomachs of animals ranging from penguins and albatrosses to well-known jellyfish eaters such as the mola mola (moonfish) and leatherback turtles.

As Haddock noted, "There is a misconception that jellies are merely a nuisance and serve no real purpose in marine ecosystems. Our results and other studies around the world show that they are a common source of food for a diverse group of predators. Interactions involving gelatinous predators and prey create most of the complexity that we see in our new deep-sea food web."

Observations made in the ROVs’ footage offer a very different perspective on deep-sea food webs than other research methods. But as Haddock explained, "Our results don’t replace the traditional ideas of a food web, but complement them. It’s as if we had a transportation map that only showed train tracks, but now we can see the rest of the roads and paths.”

The current study is reminiscent not only of the fact that marine food webs are extremely complex, but also that many deep-sea animals are eaten by animals near the sea surface. According to it, deep-sea animals are “the most important food source for many commercially important predators such as tuna,” meaning that those who eat a tuna sandwich for lunch could also be part of a deep-sea food web...

More Information: www.mbari.org

Link to the study: rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/../20172116

Video: youtu.be/TbGtPGFXEVc

Herbert

Herbert 19th December 2017

19th December 2017