Together with a handful of like-minded people I make my way to British Columbia. Via Vancouver, we drive to Shuswap Lake and wait for the sockeye salmon. We plan to stay for three weeks.

At the end of their lives, the salmon spawn in the same river they were born in. They have to swim from the ocean all the way across the Fraser River and the Thompson River, up to the source river they came from. One of these source rivers is the Adams River, which flows into the Shuswap Lake. At the Shuswap Lake they rest before heading up the fast-flowing Adams River to find their spawning grounds. Here they were born and here they will die.

The construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway caused heavy rockfall in 1914 at "Hells Gate", a bottleneck on the Fraser River. The river was blocked for a long time, interrupting the annual Salmon Run. Only a few fish managed to overcome the blockade and made it to spawn in the source rivers. After a good two years the rockfall was eliminated, and the salmon were able to travel to their spawning grounds again.

To date, the number of salmon is very different, and there is only a particularly intense run every four years. This year it is time once again. The prediction is 7 - 14 million fish.

The Canadian autumn is often wet and rainy, but we are incredibly lucky as it only rains on the day of arrival. On the afternoon of the second day the cloud curtain clears and the sun comes out, but it's getting cold, the first frosty nights are ahead of us, but thanks to the perfectly coordinated Mares equipment, I spend the whole day at the river without a moment of freezing. Even the dives in Shuswap Lake, in only 6°C - 7°C water, feel comfortable. We change location every day to give everyone from the group the chance to get photos in good conditions.

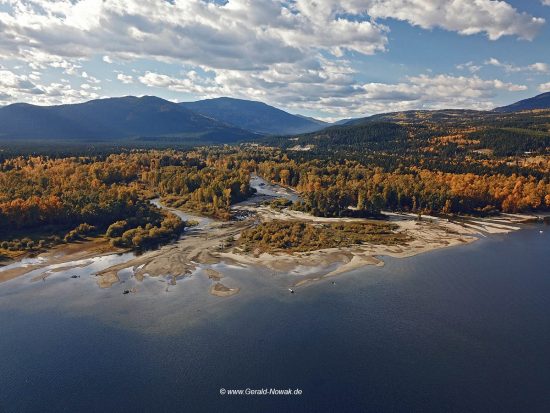

The dive site on the lake is right at the mouth of the Adams River. Here the lake has pushed a wide gravel tongue into the lake. The current in the river makes diving impossible, but if you dive sideways along the gravel, you can hardly feel the current. Here, a huge school of sockeye salmon waits to gather enough strength to fight against the current of the river and conduct the arduous trip to the tributary of the Adams River. It is a great feeling to be in the midst of the swarm but it is laborious, because only those who hold their breath for a long time can experience the salmon. Any quick movements or exhaling is enough to drive them away.

Taking photos in the river is quite different. Here, the term "dry diving" gets a whole new meaning, we are very far from a real dive. We have dry suits, but are only equipped with a mask and snorkel, no fins. We are mostly on the gravel, with only our heads and cameras in the water. The aim is to photograph the fish in the super-shallow tributaries of the river while spawning. Best as a split image, ideally with the movement of the water. It's exciting to watch the salmon defend their "place" in the river. The females bite their competitors with all their might, but even the male’s fight without ceasing.

During their way up the river, their appearance has changes tremendously. The red colour of their bodies is an attestation of the imminent end of life. Their lower jaws are bent upwards and huge teeth come to light. Many have visible injuries from their fierce fighting for females.

Female sockeye salmon build new spawning pits three to five times during spawning days, then drop several hundred eggs into them - up to 3,000 per salmon. The up to 7kg males then try to distribute their sperm over them.

The eggs stay in the gravel for several weeks before the tiny salmon hatch. They drift with the current down into the Shuswap Lake. Here they spend an average of one year until they are big enough to swim over one thousand kilometers down into the bay of Vancouver.

Once in the sea, a three-year voyage begins, first into the northern polar sea and later back to the Adams River to end the life cycle. Not all salmon have a life cycle of exactly four years. There are some who already come back after three years, while others need five years, but spawning time is always in October, usually around the 15th of the month. A few salmon never migrate into the sea, they spend their entire lives in the lake. The Aborigines of Canada, the First Nations, call these salmon "Kokanee".

We spent the three very intensive weeks oberserving the living and dying salmon. We also learned a lot about their importance for the whole region. Without the salmon the landscape would look completely different. The animals carry important nutrients from the ocean in their bodies, which after their death contribute to the survival of the entire environment of the rivers. Hardly any other region has so many eagles, sea birds and land animals that feed on the carcasses of the fish.

Only the shy black bears didn't run out in front of our lenses. They shy away from encounters with humans and only come out of their caves at night. We only ever saw their legacies, which Darryl, our local guide, gestured at with a wave of his hand: "Bear poo, you can recognize it on the berrys".

Gerald

Gerald 22nd November 2018

22nd November 2018 Adams River Salmon Run, Squilax-Anglemont Road, Columbia-Shuswap F, Britisch-Kolumbien, Kanada

Adams River Salmon Run, Squilax-Anglemont Road, Columbia-Shuswap F, Britisch-Kolumbien, Kanada